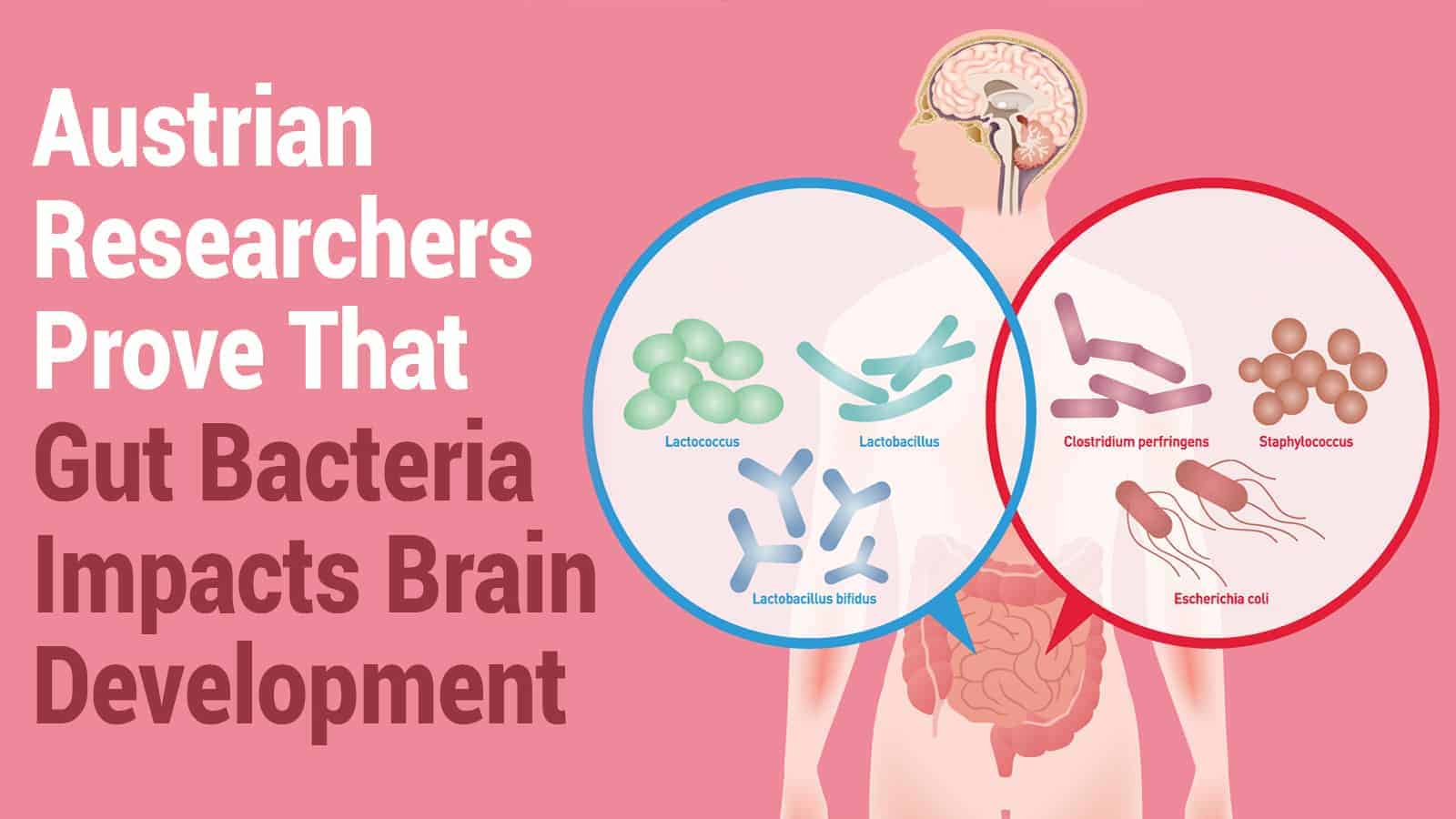

A new study shows that gut bacteria impacts brain development in premature infants. The research performed by the University of Vienna reveals that highly premature infants have a higher risk of brain damage.

Premature births have been rising worldwide and remain the leading cause of perinatal mortality and morbidity. While recent advances in medical care have increased the survival rates of premature infants, many survivors suffer from lifelong brain damage.

The researchers have discovered that targeting certain gut bacteria may help with the early treatment of brain damage. They found that an overgrowth of the bacterium Klebsiella in the intestinal tract increases specific immune cells. It also raises the likelihood of neurological damage in premature babies.

The study, published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, reveals the complexity of the gut-brain relationship. The gut, brain, and immune systems all affect each other since they’re closely related. Researchers call this the gut-immune-brain axis.

Bacteria in the gut influence the immune system and also monitors gut microbes and responds to them. The gut also connects with the brain via the vagus nerve in addition to the immune system.

“We investigated the role this axis plays in the brain development of extreme preterm infants,” says the first author of the study, David Seki. “The microorganisms of the gut microbiome — which is a vital collection of hundreds of species of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes — are in equilibrium in healthy people. However, especially in premature babies, whose immune system and microbiome have not been able to develop fully, shifts are quite likely to occur. These shifts may result in negative effects on the brain,” explains the microbiologist and immunologist.

Patterns in the microbiome may indicate brain damage

“In fact, we have been able to identify certain patterns in the microbiome and immune response that are clearly linked to the progression and severity of brain injury,” adds David Berry, microbiologist and head of the research group at the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science (CMESS) at the University of Vienna.

“In fact, we have been able to identify certain patterns in the microbiome and immune response that are clearly linked to the progression and severity of brain injury,” adds David Berry, microbiologist and head of the research group at the Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science (CMESS) at the University of Vienna.

He’s also the Operational Director of the Joint Microbiome Facility of the Medical University of Vienna and University of Vienna. “Crucially, such patterns often show up prior to changes in the brain. This suggests a critical time window during which brain damage of extremely premature infants may be prevented from worsening or even avoided,” he says.

Comprehensive study showing how gut bacteria influence brain development

The interdisciplinary team identified specific biomarkers that could help with the development of new treatments.

“Our data show that excessive growth of the bacterium Klebsiella and the associated elevated γδ-T-cell levels can apparently exacerbate brain damage,” explains Lukas Wisgrill, Neonatologist from the Division of Neonatology, Pediatric Intensive Care Medicine and Neuropediatrics at the Department of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at the Medical University of Vienna.

“We were able to track down these patterns because, for a very specific group of newborns, for the first time, we explored in detail how the gut microbiome, the immune system, and the brain develop and how they interact in this process,” he adds.

The study included 60 premature infants born before the standard 28 weeks gestation period. They weighed less than 1kg for several weeks or even months. The team utilized revolutionary scientific techniques such as 16S rRNA gene sequencing to study the microbiome, among other methods. They analyzed blood and stool samples, brain wave recordings (e.g., aEEG), and MRI images of the infants’ brains.

Premature babies have vital differences in gut bacteria.

Babies born before the third trimester have different neural circuitry due to various environmental cues. One of these includes microorganisms immediately colonizing the gut, influenced by the many neurons in the nervous system. Mounting evidence shows that during early development, enteric microorganisms receive signals from both the gut and brain.

Premature babies have a higher risk of developing perinatal white matter injuries (PWMI). Scientists have learned that perinatal infections and subsequent inflammation play a role in PWMI and can make brain injuries worse. This may lead to life-long problems such as cognitive and motor function delay, cerebral palsy, neurosensory difficulties, and ADHD.

To prevent excessive inflammation, the developing immune system and gut microbiome must remain balanced. However, in extremely premature babies, the gut microbiota and its host have significant impairments. It’s still unclear if the impaired relationship results from early-life intensive medical care or missing immunological cues.

The neonatal gut houses an abundance of γδ T cells, which stand out among T cells due to their flexible receptor chains. Scientists have observed these cells in brain lesions of premature babies with white matter injury, suggesting they may play an essential role in mediating gut-brain axis communication.

The research will continue with two studies in the future.

The inter-university cluster project was a collaborative effort by Angelika Berger (Medical University of Vienna) and David Berry (University of Vienna). The comprehensive study marks the beginning of a research project thoroughly investigating how the microbiome impacts brain development in premature infants. Also, the researchers will follow up with the children in the original study.

“How the children’s motoric and cognitive skills develop only becomes apparent over several years,” explains Angelika Berger.

“We aim to understand how this very early development of the gut-immune-brain axis plays out in the long term. The children’s parents have supported us in the study with great interest and openness,” says David Seki. “Ultimately, this is the only reason we were able to gain these important insights. We are very grateful for that.”

Final thoughts on how gut bacteria may play a critical role in babies’ developing brains

Final thoughts on how gut bacteria may play a critical role in babies’ developing brains

An Austrian study shows that premature babies have different gut bacteria than babies born at full-term. Specifically, they have an overabundance of the bacterium Klebsiella, which increases the risk of brain damage in preterm babies.

The team hopes that identifying patterns in the gut-immune-brain axis will lead to better treatments for brain damage. Targeting this bacteria may improve outcomes for premature babies born with neurological damage.