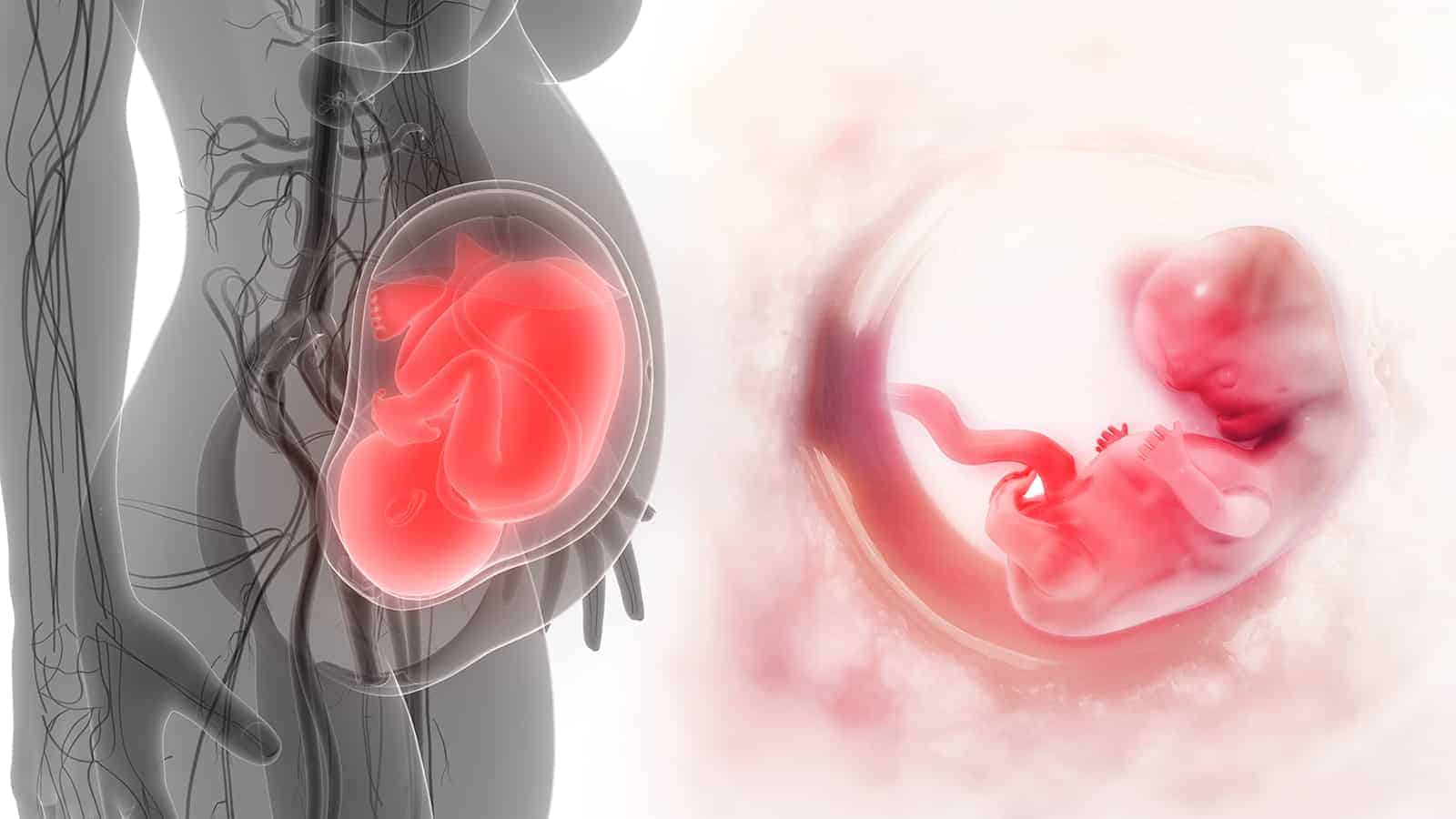

Scientists confirm that mothers and children share a biological connection known as fetal-maternal microchimerism. This means that a developing baby’s cells travel into the mother’s bloodstream and circulate back to the baby. The term microchimerism comes from the word chimera, mythical creatures made from various animals in ancient Greek mythology.

In biology, it means “an organism containing a mixture of genetically different tissues.” In a way, we’re all chimeras since our DNA comes from both our mothers and fathers.

We know that pregnant mothers pass nutrients and DNA through the placenta to their unborn children. However, scientists have also found a child’s genetic material in mothers long after pregnancy, even decades later.

The evidence scientists discovered

Scientists have found evidence that all pregnant women possess some of their child’s fetal cells and DNA. In fact, up to 6% of free-floating DNA in the mother’s blood plasma comes from the fetus. While these numbers decline after the baby is born, some cells remain in the mother. In the 1990s, a team of researchers from Tufts Medical Center found male fetal cells in a mother’s blood 27 years postpartum.

Scientists have found evidence that all pregnant women possess some of their child’s fetal cells and DNA. In fact, up to 6% of free-floating DNA in the mother’s blood plasma comes from the fetus. While these numbers decline after the baby is born, some cells remain in the mother. In the 1990s, a team of researchers from Tufts Medical Center found male fetal cells in a mother’s blood 27 years postpartum.

These fetal cells can act like stem cells, morphing into different cell types to help repair damage in their mothers’ organs. The cells can influence a mother’s long-term health and explain why prior pregnancy can protect women against diseases like breast cancer.

This suggests that even before birth, babies have an innate instinct to survive. By looking out for their mother’s health, it ensures the baby can develop safely. Fetal microchimerism also helps the mother heal from potentially deadly diseases. Scientists have found that stem cells can develop into epithelial cells, specialized heart cells, liver cells, and even neurons.

However, while fetal cells can enhance a mother’s health, a 2015 study found that microchimerism can also negatively affect. Arizona State University researchers discovered that the cells could act cooperatively or competitively, depending on the circumstance. They’ve been linked to protection and increased risk of many diseases, such as cancer and autoimmune disorders.

How fetal microchimerism impacts a mother’s health

This phenomenon can be found across mammal species, such as in dogs, mice, and cows. Scientists have just begun to understand this alien concept and how it impacts both mother and baby. When the ASU scientists reviewed published studies on fetal microchimerism, they discovered the true complexity of fetal cells.

For the study, they applied an evolutionary framework to predict the behavior of fetal cells. This would help them understand when the cells benefited the mother and led to adverse effects. They found that fetal cells don’t just migrate to maternal tissues; they also act as placenta outside the womb. The cells redirect essential nutrients and genetic material from the mother to the developing fetus.

How it works

In short, there’s a constant tug-of-war between the mother’s and child’s interests. There’s also a mutual desire to survive, which requires cooperation between the baby and mother. The mother passes vital nutrients to her baby, and the fetus passes DNA to the maternal system.

If fetal microchimerism benefits maternal and offspring survival in most instances, it will become part of evolutionary adaptation. The review of existing data found that fetal cells have a cooperative relationship with maternal tissues in some cases. In other instances, the fetal cells compete for resources, or they may exist as neutral entities. Scientists believe that the cells likely play all of these roles in various situations.

For instance, fetal cells may lead to immune responses and even autoimmunity if the mother recognizes them as foreign bodies. They may explain the increased autoimmunity rates in women. For example, rheumatoid arthritis occurs three times as often in women as men.

Fetal microchimerism can also benefit the mother, even helping heal wounds from caesarian incisions. This shows that fetal cells play an active role in repairing tissues in the mother. However, the cells may also enter a mother’s bloodstream and act as bystanders, neither helping nor harming the mother.

The complex nature of fetal microchimerism

The authors used a cooperation and conflict approach to help predict fetal cells’ positive or negative influence on mothers. This gave them more insight into the circumstances causing cells to cooperate or compete for resources.

According to evolutionary theory, the fetal cells will cooperate when the cost doesn’t outweigh the risk, such as tissue maintenance. However, competition is the likely outcome in situations where limited resources must be allocated between the fetus and mother. This conflict may cause harmful effects for both mother and baby.

Researchers observed the tug-of-war relationship in the fetal cells in female breasts, for instance. The cells have been detected in the breasts of over half of the women sampled. Fetal microchimerism plays an active role in breast development and lactation. While milk production ensures the baby’s survival, it also takes a lot of energy from the mother.

Scientists have found that poor lactation, a common occurrence, may stem from low fetal cell count in breast tissue. Testing fetal count in breast milk could provide concrete evidence of fetal cells’ impact on maternal health.

The relationship between breast cancer and fetal cells is also a complicated matter. Scientists found that women with breast cancer tend to have a lower fetal cell count. However, some data shows that fetal cells may increase breast cancer risk for several years after a woman gives birth.

Finally, fetal cells may also impact a woman’s thyroid function. Fetal cells have been found more frequently in the blood and thyroid glands of women with thyroid diseases, including Hashimoto’s, Graves’ disease, and thyroid cancer. The study authors believe that a women’s immune system may overact when controlling fetal cell influence. This could lead to high levels of autoimmunity and inflammation, contributing to autoimmune disease.

Final Thoughts: Fetal cells affect a mother’s health during pregnancy and beyond

Final Thoughts: Fetal cells affect a mother’s health during pregnancy and beyond

Fetal cells can travel into a mother’s bloodstream and circulate back to the baby, also known as fetal-maternal microchimerism. This phenomenon has been observed in all placental mammals. However, scientists are just beginning to unravel the complicated relationship between a mother and her developing fetus.

It’s clear that researchers will need to continue studying fetal microchimerism, as it’s a highly complex topic. They hope that future studies will lead to improvements in diagnosing conditions and predicting long-term maternal health.