Researchers at Wellcome Sanger Institute and European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) have identified over 142,000 virus species in the gut. Over half of them have never been detected until this study. This may seem like many viruses, but it pales in comparison to the total number on our planet.

According to studies, an estimated ten nonillion (10 to the 31st power) individual viruses live on Earth. This equates to one virus for every star in the universe, 100 million times over. However, most of them don’t pose a threat to humans; in fact, some are beneficial to our gut microbiome. Scientists have just begun to understand how gut bacteria affect humans and how we can improve our microbiome.

The paper published in February of 2021 in Cell contains an analysis of over 28,000 gut microbiome samples collected throughout the world. The researchers found an unexpectedly high number and diversity of viruses in various parts of the globe. This data will spawn new research about how viruses in the human gut impact our health.

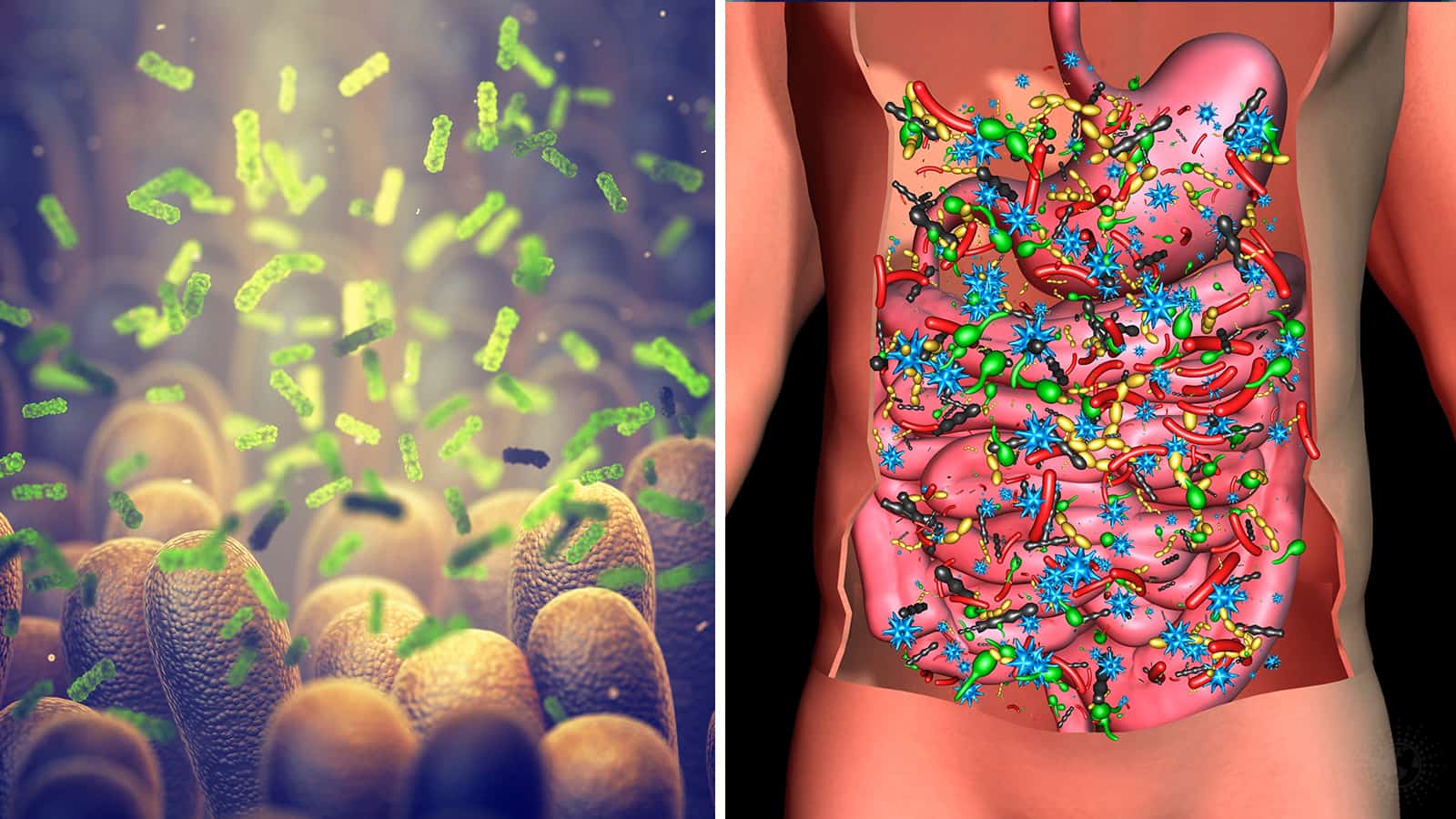

The amazing human gut microbiome

The human gut houses a highly diverse environment filled with various bacteria and viruses. In fact, hundreds of thousands of viruses, called bacteriophages, live in the gut and can infect bacteria. Scientists have recently discovered how gut dysbiosis can cause obesity, diabetes, stomach issues, and even allergies. However, they have just scratched the surface in understanding the complex human gut and its impacts on our health.

In this study, researchers found over 70,000 virus species living in the gut that have never been identified before. They used a DNA-sequencing method called metagenomics to identify and categorize the virus species. Researchers from the two institutes analyzed 28,060 public human gut metagenomes and 2,898 bacterial isolate genomes from the gut. From this massive analysis, researchers identified about 142,000 virus species in the human microbiome.

Researchers hope to learn more about how the virus species affect human health.

Most of the viruses living in the gut are harmless to humans. We need them to survive, as they hold crucial genetic material that we need to function. As many species have not been identified until now, more research is needed to understand them better.

Dr. Alexandre Almeida, Postdoctoral Fellow at EMBL-EBI and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “It’s important to remember that not all viruses are harmful, but represent an integral component of the gut ecosystem. For one thing, most of the viruses we found have DNA as their genetic material, which is different from the pathogens most people know, such as SARS-CoV-2 or Zika, which are RNA viruses. Secondly, these samples came mainly from healthy individuals who didn’t share any specific diseases. It’s fascinating to see how many unknown species live in our gut and to try and unravel the link between them and human health.”

Among the 140,000 virus species, researchers found a new, highly pervasive clade – a group of viruses with a common ancestor. The scientists referred to it as the Gubaphage, which they identified as the second most prevalent clade in the gut. The crAssphage, found in 2014, is the most ubiquitous; some studies estimate that 73-77% of humans have it.

Both viruses appear to infect similar strains of gut bacteria. However, researchers will need to do more studies to understand precisely how the Gubaphage functions. They believe this study will pave the way for important discoveries in the future.

How the bacteriophage virus species can treat diseases and prevent foodborne illness

Dr. Luis F. Camarillo-Guerrero, the first author of the study from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “An important aspect of our work was to ensure that the reconstructed viral genomes were of the highest quality. A stringent quality control pipeline coupled with a machine learning approach enabled us to mitigate contamination and obtain highly complete viral genomes. High-quality viral genomes pave the way to understand better what role viruses play in our gut microbiome, including the discovery of new treatments such as antimicrobials from bacteriophage origin.”

They recorded the results in the Gut Phage Database (GPD). This database contains an organized catalog of 142,809 non-redundant phage genomes. Researchers can refer to this when studying bacteriophages and how they impact the human gut and our health.

Dr. Trevor Lawley, the senior author of the study from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: “Bacteriophage research is currently experiencing a renaissance. This high-quality, large-scale catalog of human gut viruses comes at the right time to serve as a blueprint to guide ecological and evolutionary analysis in future virome studies.”

Previous studies on this subject foretold this outcome

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh discovered firsthand how the bacteriophage virus species could treat disease a few years ago. They successfully treated 15-year-old cystic fibrosis patient Isabelle Carnell-Holdaway, who’d been battling a drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus infection half her life. While her infection isn’t cured, the bacteriophage treatments seem to have made it more manageable. The research was published in the journal Nature Medicine in May 2019.

A 2017 article by Veerasak Srisuknimit on the Harvard University blog wrote, “Now that more and more bacteria have developed resistance to antibiotics, scientists around the world have a renewed interest in phages. The European Union invested 5 million euros in Phagoburn, a project that studies the use of phages to prevent skin infections in burn victims. In the USA, the FDA approved ListShield, a food addictive containing phages that kill Listeria monocytogenes, one of the most virulent foodborne pathogens and one cause of meningitis. Currently, many clinical trials using phage to treat or prevent bacterial infections such as tuberculosis and MRSA are undergoing.”

Final thoughts: Scientists found over 140,000 virus species in the human gut

Final thoughts: Scientists found over 140,000 virus species in the human gut

In this groundbreaking study, researchers identified over 70,000 viral species that have never before been discovered. They say that most of them are not pathogens but hold DNA integral to a functioning microbiome. Researchers believe that future studies will provide even more clues about how these viral species affect us. Indeed, they believe future projects will uncover even more virus species in the gut.