A new study by UC Irvine researchers reveals a new molecular pathway that could accelerate wound healing. The research specifically focused on the recovery of wounds in the skin. The molecular path identified, called Fascin Actin-Bundling Protein 1 (Fscn1), becomes activated by a Grainyhead like 3 (GRHL3) gene. When this occurs, it relaxes the adhesion between wounded skin cells, and the protein-coding genes work to close the wound.

GRHL3, an evolutionarily conserved gene, plays a considerable role in mammalian development. If a mammal lacks this gene, various abnormalities can occur. These include rare conditions like spina bifida, defective epidermal barrier, defective eyelid closure, and soft-tissue syndactyly, which causes fused or webbed fingers in children.

More about the pathway that could speed up wound healing

The study, published in the journal JCI Insight, reveals how GRHL3 activates Fscn1 to loosen adhesions between migrating keratinocytes during wound healing. Keratinocytes, the most prevalent cells in the epidermis, play critical roles in wound repair and immune function. They execute the re-epithelialization process, where keratinocytes migrate, multiply, and differentiate to repair the epidermal barrier.

What the Researchers Found

Researchers found that when this process becomes altered, it may lead to chronic, non-healing wounds. An example of this is diabetic ulcers, which impact millions of people every year.

Researchers found that when this process becomes altered, it may lead to chronic, non-healing wounds. An example of this is diabetic ulcers, which impact millions of people every year.

“What’s exciting about our findings is that we have identified a molecular pathway that is activated in normal acute wounds in humans and altered in diabetic wounds in mice,” said Ghaidaa Kashgari, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in the UCI School of Medicine Department of Medicine. “This finding strongly indicates clinical relevance and may improve our understanding of wound healing biology and could lead to new therapies.”

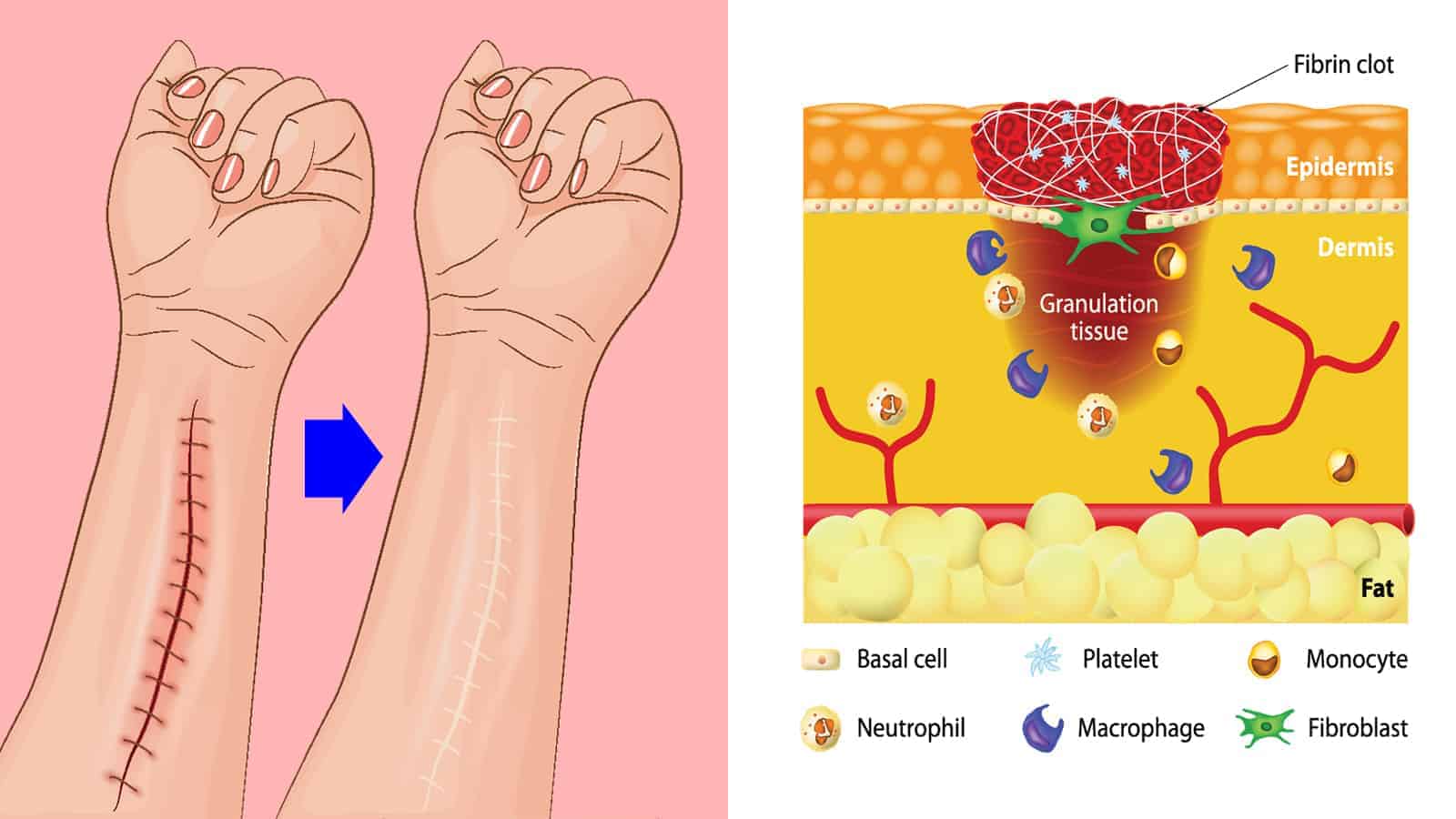

Wound Healing Occurs in Stages

Acute skin wound healing consists of four overlapping phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and tissue remodeling. In the first stage, blood begins to clot to help stop bleeding. Then, white blood cells migrate to the wound site to help defend and clean the area. Finally, the body works on rebuilding and repairing the tissue.

While dermal contraction causes wounds to partially close, reepithelialization plays a significant role in wound healing. This process occurs during the proliferation phase.

During wound healing, keratinocytes, found primarily in the outer layers of the skin, migrate on top of the underlying granulation tissue. This lumpy, pink tissue forms around the edges of a wound. Then, the keratinocytes merge with migrating keratinocytes from the opposite side to close the wound.

“Despite significant advances in treatment, much remains to be understood about the molecular mechanisms involved in normal wound healing,” said senior author Bogi Andersen, MD, a professor in the Departments of Biological Chemistry and Medicine at the UCI School of Medicine. Department of Biological Chemistry and Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology. “Our findings uncover how abnormalities in the GRHL3/FSCN1/E-cadherin pathway could play a role in non-healing wounds, which needs to be further investigated.”

The National Institutes of Health and the Irving Weinstein Foundation helped fund this study.

The four stages of wound healing

Here is how the wound healing process works.

Stage 1: Stop the bleeding (hemostasis)

When you suffer from an injury, you may bleed, depending on the severity. The body’s first line of defense involves stopping the bleeding, called hemostasis. In mere seconds, blood starts to clot to reduce blood loss. Clotting can also help with wound healing since it causes the injury to scab over.

Stage 2: Defending the area (inflammation)

You hear all sorts of bad things about inflammation, but it’s a critical part of wound healing. This causes blood vessels near the wound to open more so that blood flow increases. Thus, the expansion allows more oxygen and nutrients into the wound to begin to heal. The injury will start to look red, inflamed, or swollen, which means it’s healing.

White blood cells known as macrophages migrate to the wound to clean it and fight off infection. In addition, they release chemical messengers called growth factors to help repair the tissue. If you see clear fluid oozing out of the wound, it’s a sign that the white blood cells have begun the rebuilding process.

Stage 3: Rebuilding (proliferation)

After your body cleans the wound and wards off infection, it can start rebuilding the tissue. Red blood cells rich in oxygen help with wound healing by creating new tissue. Chemical messengers alert cells near the wound to produce collagen, a critical component in repairing the injury. At this stage, your wound will start forming a raised, red scar.

Stage 4: Tissue remodeling

Now your body has made it to the maturation or strengthening phase. The wound will probably appear pink, and the skin over it may look stretched. This pinkness is a good sign because it means the wound is almost healed. Over time, the redness will fade, and inflammation will subside, but it may leave a scar depending on the injury.

As the body’s largest organ, the skin helps protect your internal organs and keeps vital nutrients in the body. It also provides a barrier against harmful substances and shields the body from too much radiation emitted by the sun. When you get a skin injury, it also ensures you heal properly by sending essential proteins to the wound site. The cells help close the wound and keep infections at bay.

While more research is necessary to understand keratinocytes’ role in wound healing, this study marks a huge breakthrough. Now, scientists know that two genes, GRHL3 and Fscn1, work together to close wounds and promote healing.

Final Thoughts: UC Irvine researchers reveal new molecular pathway in wound healing

Final Thoughts: UC Irvine researchers reveal new molecular pathway in wound healing

Scientists recently found that a molecular pathway involving two genes plays a critical role in wound healing. It becomes activated in normal acute wounds, but alterations in this pathway can cause chronic injuries. In people with diabetic ulcers, for example, keratinocytes don’t function properly. Researchers will need further studies on keratinocytes’ immune functions in wound repair and chronic wound pathology.

However, this study hopes that a better understanding of molecular pathways involved in wound healing will lead to improved therapies.